Episode 4: Forms Hook Functions

Appreciating the interplay between intent and tangible experience

In this episode:

Swatchbooks as Prototyping Archive, by Nicole Yi Messier

Aliens, Architecture and Limbo-Worlds, by Dana Karwas

The Future of Audience, by Laura Frank

Preamble

We are in a new era, where parametric design allows us the flexibility to create new forms of non-rectilinear footprints. Simultaneously, materials are evolving to provide both permeable and reactive surfaces.

We need new tools and techniques, and perhaps resurrect old tools and revisit old approaches, to create the next wave of compelling experiences.

In this episode we explore how tangible form intersects and interplays with both intended and experienced function. This is not about the (rather pointless) debate of whether form or function comes first. It’s about recognizing that the end engagement is crafted by leveraging both form and function in interesting and unexpected ways.

That is, after all, at the heart of the design of experiences.

Swatchbooks as Prototyping Archive

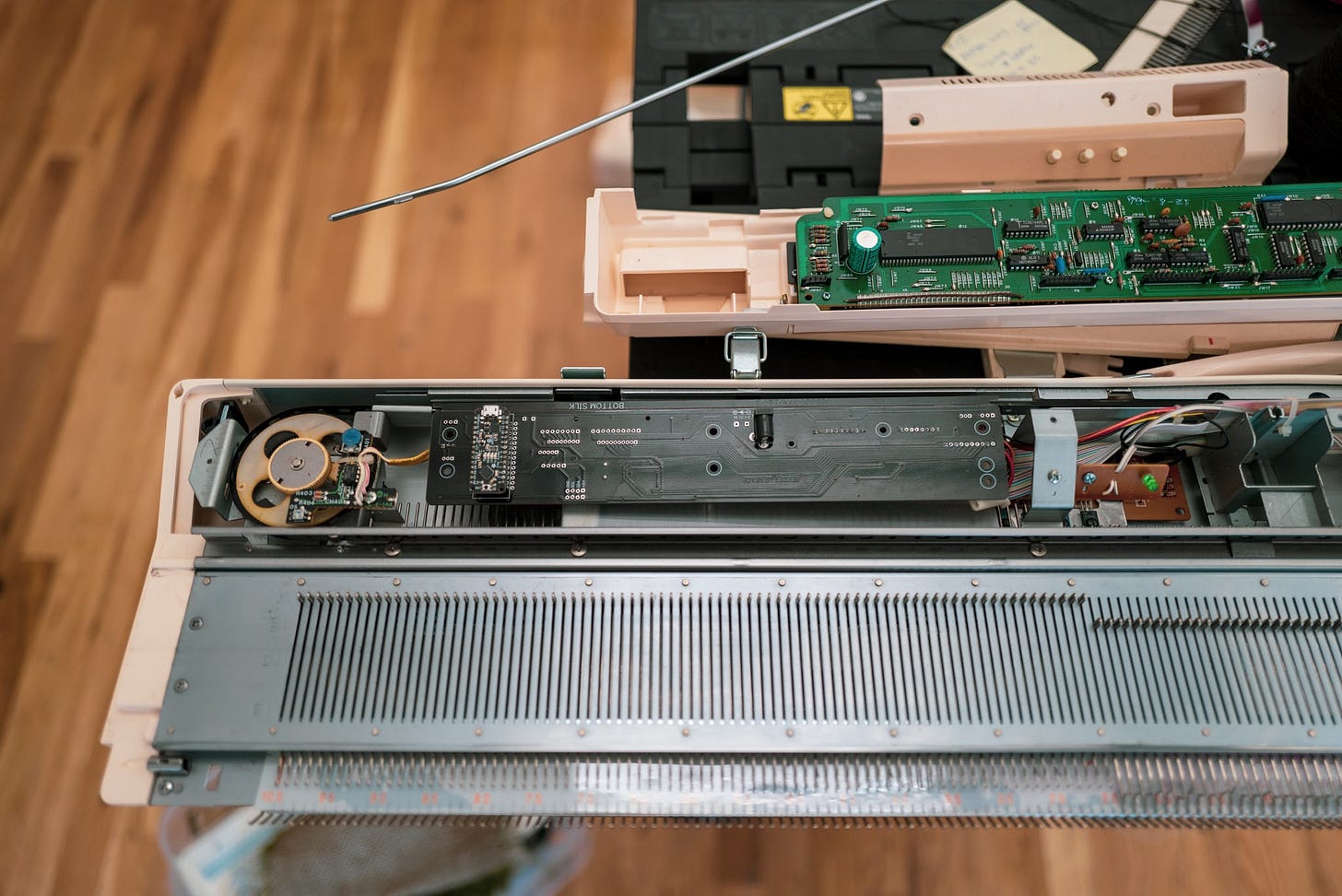

When I explain to people that I’m using a knitting machine, they quickly assume that the machine does all of the making. In reality, it’s a collaboration between the user and machine. This is my favorite part — each step is facilitated by the user through casting on, moving the carriage, twisting stitches, fixing dropped stitches and more. The machine facilitates which needles to move, how to move them and how each thread hooks to the needles.

As an avenue to learn machine knitting, a few collaborators, Liza Stark, Victoria Manganiello and I decided to start a swatchbook to document our progress and findings as we learned how to use the Brother KH910 Electroknit Knitting Machine.

Why a Swatchbook?

Traditionally associated with craft and textile work, a swatchbook is a booklet that contains samples demonstrating a particular fabrication technique. I have been inspired by The E-Textile Summer Camps Swatchbook Exchange, “a platform for sharing physical work samples in the field of electronic textiles. Individuals and collaborative efforts participate in the exchange by submitting a unique swatch design of their own, and in turn receive a compiled collection of everybody else’s swatches. The exchange wishes to emphasize the importance of physicality and quality workmanship in an increasingly digital world”. I’ve never participated in the swatch exchange, but I have had the pleasure of looking through a few iterations of the swatchbook. When you hold the booklet, it feels full and bulky — filled with samples of eTextile swatches. The book possesses a presence as part art artifact, documentation and community sharing.

A Tour of Our Swatches

Machine Knitting 101

To kick off our machine knitting swatches, we started with the basics. First up, learning how to cast on and off the machine. We tried the cast-on comb and e-wrap cast-on methods, and the loop-through-loop and latch-hook bind off methods. As a group, we all quickly gravitated towards our favorites, typically choosing different approaches. After multiple iterations of our cast-on and cast-off methods were solid, we tried eyelets, ladders, a simple hem and a honeycomb pattern.

AYAB

The 3D structure of the honeycomb swatch left us wanting to explore and experiment creating varying knitted textures and patterns. We decided to use the knitting machine needles to transform our swatches into soft pixels with All Yarns Are Beautiful (AYAB). AYAB is an open-source project that provides an alternative way to control the Brother KH-9xx range of knitting machines.

The KH-910 knitting machine was originally created and programmed to use semi-transparent picture cards that are scanned by the machine. Using the line-by-line data, the machine changes the needle positions to knit the image on the picture card. The picture card is two-toned (white and black), and each knitted pixel can be represented using two different-colored yarns. Using the AYAB hardware, the knitting machine can be connected to a computer and a digital image can be uploaded.

The AYAB hardware comes in two forms, a custom-developed shield for arduino or the AYAB interface created by Evil Mad Scientist Laboratory. To use the interface, you simply open the knitting machine and replace its control board with the AYAB controller. The interface pairs with the AYAB software.

Visiting upstate New York for a week of making, we decided to use our surroundings as inspiration and set up the knitting machine in the front yard. We took a photo of the bark on a tree in front of us, turned the image to a pure black and white scale, and knitted the outcome.

Knitted eTextile Swatches

Electronic textiles, or eTextiles, embed electronics and electrical circuits into textiles using conductive fabrics, yarns, threads and other materials through craft, fabrication or industrial techniques. For our knitted eTextile swatch, we decided to start with a simple design to see how the machine would work with copper thread. Copper thread is much stiffer compared to yarn, so we had our doubts. The design consisted of two circuit paths (i.e., leads) of copper thread knitted in the middle of our swatch. Each copper path was coupled with thin yarn as a reinforcement.

Next, we decided to create a knitted stretch sensor. A knitted stretch sensor is made of conductive yarn, and when stretched, the resistance of the material changes.

Our initial design was to create a square swatch with a long tube in the middle that could be pulled (picture a sock in the middle of a knitted square). The tube would be created using conductive yarn and the square base would be created using regular yarn. We wanted the piece to be knit in one pass and did not want to attach two separately knitted pieces together. Not knowing exactly where to start, we browsed through Knitting Techniques Book by Brother Industries Ltd., 1984 and decided to try partial knitting.

After a few attempts of partial knitting, the tube structure was more of a hammock structure with two holes on each side. Looking at our “failed” swatch, we realized these hammocks were perfect finger pockets. With two pockets on each swatch, two fingers could sit in each hammock and stretch the material — this would create two knitted stretch sensors that could be used as analog inputs with an arduino board. Excited by this, we quickly wrote up a pattern for a Knitted Finger Pocket Stretch Sensor. Inspired by how Annie Larson writes her knitting patterns, we drafted ours using them as a reference. Below you will find the pattern for the Knitted Finger Pocket Stretch Sensor. R# refers to row # (i.e. R0 == the first row, typically the row that is casted on).

R0 - Cast On (e-wrap or latch tool; carriage starts on right side)R1 - R16: KNIT -- Set up Partial Knitting; Set carriage to “H” ; Bring needles 1-20 and 30-50 to E positionR17 - R42 KNIT Watch out for dropped stitches here. -- Set carriage to “N”R43 - R58 KNIT-- Set up Partial Knitting; Set carriage to “H” ; Bring needles 1-20 and 30-50 to E positionR59 - R84 KNIT Watch out for dropped stitches here. -- Set carriage to “N”R85 - R100 KNIT-- Bind off. Consider knitting the final row at a larger gauge to aid bind off. Why a Knitting Machine?

Working with the swatchbook approach is helping us learn what is possible with the machine. By learning new techniques, we are inspired by how the material and machine work together, discovering new ways to experiment along the way. We plan to create a full swatchbook with many experiments. Follow us along @etextiles to see our progress.

References:

The E-Textile Summercamp’s Electronic Textile Swatch Exchange

Knitting Techniques Book by Brother Industries Ltd., 1984

Aliens, Architecture and Limbo-Worlds

I recently attended a housewarming party at a curious building in Guilford, CT: A 300-foot-long spaceship, clad in lead-coated copper, that rests three stories high on a series of concrete columns. Nestled perpendicular to the beach overlooking the Long Island Sound and built in the 1980s, the spaceship’s architecture demands attention, sited as it is on a hill and threatening to take off amid the neighboring New England colonials. For the spaceship, its other-worldly form lives in architectural solidarity with Peter Cook’s Kunsthaus Graz, the Friendly Alien building in Graz, Austria and brings life to Ron Herron’s vision of the “Walking City” for Archigram.

Before I knew people lived in the spaceship, I figured it was some type of futuristic organization or a defense lab that had to be shaped accordingly due to the large alien being held captive inside. Before the party, I imagined talking among friends while suspended in an unrecognizable layout of mysterious interior dimensions. Would there be a dining room? A kitchen? What about stairs, ramps or portals? I am guessing the furniture would be custom? At the same time I imagined the building offering some kind of maternal architectural embrace that was different than conventional architectural form and function.

Upon ascending the tiny stairs up to the entry portals to the condos, I was surprised to find out that the living spaces were segmented into regular shapes — with mostly right angles! — and layouts by and large indistinguishable from the brownstone I had left in Brooklyn a few years earlier. Now that I was inside, how would I know this was a spaceship?

For me, the contrast of the interior architectural interpretation and the exterior form of the spaceship in Guilford recalled Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation. In this instance, however, the shadow-space is not one of desiccated and emotionless interpretation, but rather one of function and functionality. That shadow-space’s influence on the building’s design is revealed by the decision to make the interior more accessible, livable, familiar — no aliens here. But I couldn’t forget the emotional reaction that the form of the spaceship building evoked in me regarding the choice of materials and magic of its shape. I immediately thought of how my body would work in a space like that and assumed the interior was reflective of the exterior.

After the party, my family and I returned home to our eternal fixer-upper. It’s a small house, built in the 1960s, ostensibly an era of hopeful and starry-eyed explorers. Despite its Space Age pedigree, it was largely made of wood. There was wood shake siding, knotty pine walls, large exposed Douglas fir beams, and thick wooden doors with no window or even a peephole to look out the front.

Working incrementally towards making it our own, my family made some modest updates, mostly to the kitchen, while we pondered our next move. We still have no way to see out our front door, but, after considering the space between the kitchen and the foyer and channeling my best Gordon Matta-Clark, I had our obliging contractor cut a perfect circle into a kitchen wall.

Initially, the incongruousness of the circle’s perfection felt humorously at odds with the house. But as the days passed, we continued to discover new delightful aspects of its form. In the morning, it creates an ad hoc sundial as the light marches across the sky; the moon can similarly help illuminate what was otherwise a dim corridor. During gatherings, adults pass gifts or drinks through it, while toddlers delight in its opportunities for peek-a-boo. We discovered that the portal helps circulate the rhythms of our daily household, creating new, unexpected functions out of what had been a blank wall.

Thinking back on Sontag’s shadow-space, I’d like to posit a different dimension to consider, a limbo world of designs and forms and, yes, functions that haven’t been realized in the real world yet. That limbo world exists at odds with the shadow-space. Its not-yet-real forms won’t become real while the shadow-space exerts too much influence over the architect’s designs. As a result, that shadow-space shields our bodies from the possible — potentially beautiful, playful, primal responses to designs are culled away in the name of efficiency and utility.

The emotional experience of space as felt through the body and perception is where new interfaces, spatial connections and architecture can reconnect us to form. What do you see? What do you hear? Sometimes the serendipity and delight of the form does the work for us, and we simply let our bodies engage with it. That modest circle window for us was a portal into that limbo-space, allowing a new set of functions into our world to delight us. But imagine now something more monumental: A space where James Turrell’s Ganzfelds were in fact architectural cliffs of depth? Or the Random International’s Rain Room embodied an exterior form? There is a friendly alien out there in that limbo-space, waiting to show us beyond the limits of our philosophy. I’d like to meet it.

The Future of Audience

On an island in the Seto Inland Sea in Japan is a museum dedicated to a single project, the recording of human heartbeats. Beginning in 2008, Christian Boltanski recorded the sounds of heartbeats all around the world, housed in a collection called "Les Archives du Cœur."

You can find this compilation of sound files on the island of Teshima, located in the beautiful expanse of water between Osaka and Hiroshima that separates Shikoku Island from the mainland of Japan. My husband and I found ourselves there in summer of 2020, adrift in the pandemic, not certain we’d have time to visit this exhibit on a day trip to see the many museums on the island. Given another opportunity, I would not hesitate to go back.

There is only one room to see. Long and sporadically mirrored, it’s lit with a single light bulb timed to the sound of a beating heart. As part of the collection, this room’s sole purpose is to play a recording of someone’s beating heart, one of the thousands of files housed in the archive. We were slightly out of breath from the bike ride to the museum site and feeling a bit lost as to what we were about to encounter. I realized after our visit this might be why the museum is so isolated, only to amplify the transformation one experiences inside the chamber. Did it matter who this heartbeat belonged to? Not at all. We were instantly calmed, focused and present. One heartbeat faded and another started, all strangers, and each as powerfully intimate as the next.

I often find myself reflecting on this moment and the power of the sound of the human heart. Our mother’s heart is the sound we hear in the safety of the womb, yet it’s an uncommon sound for most to hear on a daily basis. However — and stick with me here for a second — heartbeat is what bonds an audience. We may not hear each other’s heartbeats, but we feel each other. We share the emotion and excitement of a performance, or the quiet study of an exhibit, because in a crowd, we synchronize our heartbeats to those in close proximity. A great lesson of the pandemic for me is that the future of audience depends on how we can feel each other.

A small amount of research has been done on the topic of heartbeat synchronization during live performance. Doctors from the UCL Division of Psychological and Language Sciences produced documentation showing audience members of a West End musical synchronizing their heartbeats with nearby strangers while watching a performance. If you’ve attended a socially distanced performance during the pandemic, this research might immediately ring true. Those six feet of separation might as well be a mile for what makes an audience resonate with itself.

Virtual audiences have produced new work ailments in 2020, like ‘zoom fatigue.’ We’ve had all manner of virtual presentations and remote performance during the pandemic. Audiences have been piped in over their phone cameras onto LED Walls, OLED Displays and via AR broadcasts, while performers can be in a green screen room in one country and a synchronized pair of cameras will make them appear present in a live presentation in another country. The technology is fantastic, but will any of these virtual audience options stick around? Will there be hybrids? Or are we all still weeping with so much joy at the thought of bumping shoulders with strangers at a rock concert that we don’t ever want to see a video screen again?

There is much in these attempts at virtual audiences that has value. Bringing art and performance to a much larger audience through remote viewing technologies should be part of our future and we should not ignore these tools in our excitement to return to live. The hook is finding the right tools that bond the audience together. The future of audience needs to sync our heartbeats over the internet or it’s just another online meeting. There is an opportunity to build audience on a much larger scale if we can find the right way to connect together virtually.

While my husband and I stood alone in the presentation room of "Les Archives du Cœur" I wasn’t aware of being isolated. The mirrors placed about the space broke apart the walls and the sound was loud enough to envelope us, filling in the space left in the room. I don’t know what the future of audience looks like, but I know I will be carefully studying the space between us as we gather again in the very near future.

— Laura Frank

Shortly after this article was written, we received news the artist Christian Boltanski passed away on July 14, 2021. The Benesse Art Museum gave tribute to the artist and the 11th anniversary of “Les Archives du Cœur” by playing a recording of the artist’s heartbeat on July 19, 2021.

Epilogue

It’s a truism that our tools limit our creativity. Everything looks like a nail to the one wielding a hammer. In experience design we constantly grapple with how to bring memorable and meaningful tangibility into the user experience, while evoking emotion through the appropriate activation of spaces.

Laura’s statement, that the “future of audience needs to sync our heartbeats over the internet… there is an opportunity to build audience on a much larger scale if we can find the right way to connect together virtually” prompts the thought of how we may need new tools to do that virtual connection. Perhaps it’s not only about connecting virtually, but also connecting in new ways. After all, we have already normalized WhatsApp’ing across a single room, and Zoom’ing between adjacent rooms!

Dana’s experience of Wilfred Armster’s Shoreline condo complex exemplifies the dissonance of one design (the circular exterior) being forcibly conformed to another (the right-angled interior). We often want a design to retain the intent of a space, but fail to deliver the end expectation by falling back on familiar approaches. I’m now curious how that spaceship’s interior could be redesigned to carry the circular intention all the way through.

Nicole’s exploration of coding a knitting machine illustrates how we could, perhaps, start creating environments through the use of older tools by adapting them for our new creative scenarios. This is where the real collaboration of form and function starts to become apparent.

This is, arguably, the promise of parametric design. We can explore new mechanisms to manifest our algorithmic designs into material solutions. And re-enliven our environments with new modes of storytelling!